Minimum MAG completeness percentage

Choosing a minimum genome completeness threshold is a critical but complex decision in de-replication and bin refinement. There is a trade-off between computational efficiency and genome quality:

- Lower completeness thresholds allow more genomes to be included but reduce the accuracy of similarity comparisons.

- Higher completeness thresholds improve accuracy but may exclude valuable genomes.

Impact of Genome Completeness on Aligned Fractions

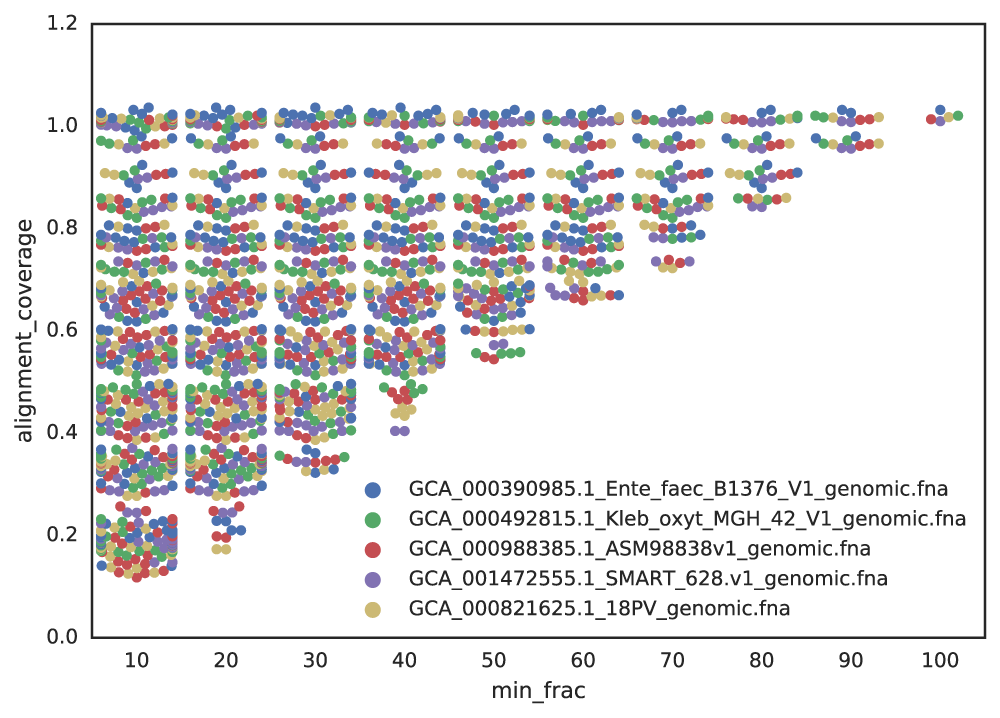

When genomes are incomplete, the aligned fraction—the proportion of the genome that can be compared—decreases. For example, if you randomly sample 20% of a genome twice, the aligned fraction between these subsets will be low, even if they originate from the same genome.

This effect is illustrated below, where lower completeness thresholds result in a wider range of aligned fractions, reducing the reliability of similarity metrics like ANI.

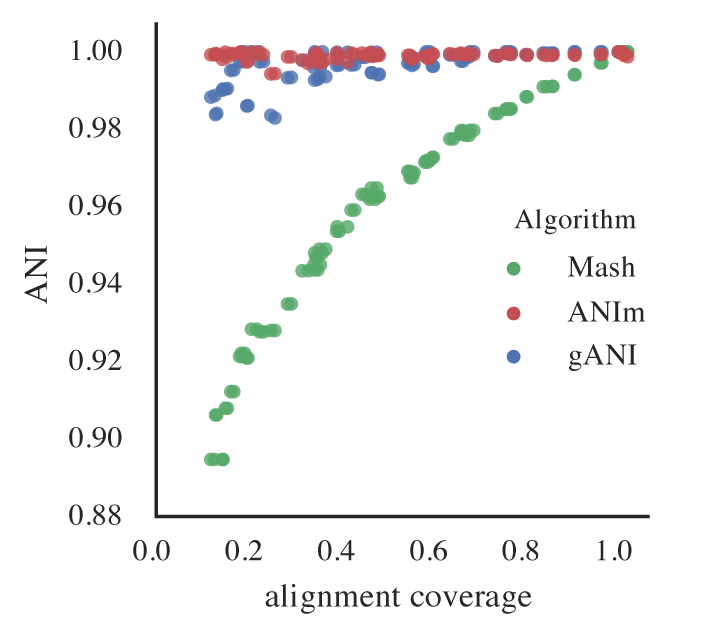

Effect on Mash ANI

Incomplete genomes also artificially lower Mash ANI values, even for identical genomes. As completeness decreases, the reported Mash ANI drops, even when comparing identical genomes.

This is problematic because Mash is used for primary clustering in tools like dRep. If identical genomes are split into different primary clusters due to low Mash ANI, they will never be compared by the secondary algorithm and thus won’t be de-replicated.

Practical Implications for De-Replication

-

Primary Clustering Thresholds:

If you set a minimum completeness of 50%, identical genomes subset to 50% may only achieve a Mash ANI of \( \approx \) 96%. To ensure these genomes are grouped in the same primary cluster, the primary clustering threshold must be \( \leq \) 96%. Otherwise, they may be incorrectly separated.

-

Computational Trade-Offs:

Lower primary thresholds increase the size of primary clusters, leading to more secondary comparisons and longer runtimes. Higher thresholds improve speed but risk missing true matches.

-

Unknown Completeness:

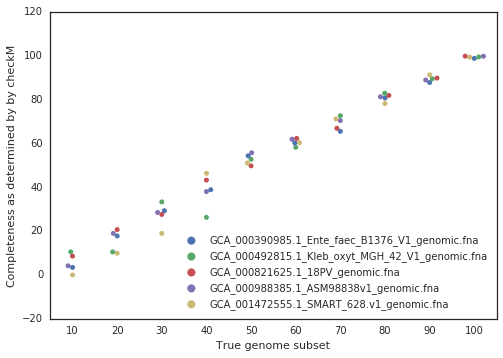

In practice, the true completeness of genomes is often unknown. Tools like CheckM estimate completeness using single-copy gene inventories, but these estimates are not perfect in particular for phages and plasmids, explaining why they are not supported in dRep. In general though, checkM is pretty good at accessing genome completeness:

Guidelines for Setting Completeness Thresholds

- Avoid thresholds below 50% completeness: Genomes below this threshold are often too fragmented for reliable comparisons, and secondary algorithms may fail.

- Adjust Mash ANI thresholds accordingly: If you lower the secondary ANI threshold, also lower the Mash ANI threshold to ensure incomplete but similar genomes are grouped together.

Balancing genome completeness and computational efficiency is key to effective de-replication. While lower completeness thresholds include more genomes, they reduce alignment accuracy and increase runtime. Aim for a minimum completeness of \( \geq \)50% and adjust clustering thresholds to avoid splitting identical genomes.